Usability Considerations

With our expanding palette of options for interactively presenting content, ensuring people can use our content remains critical. When considering the overall usability of your content, think about the impact of hiding and displaying content as well as the content’s offline uses. In describing specific usability considerations, I’ll evaluate a few specific examples of interactivity in content presentation.

Are You Using Too Much Interactivity?

RIAs (Rich Internet Applications) let users access additional content without waiting for an entire page to reload in their Web browsers. For instance, the Yahoo! home page lets me access my horoscope without going to a new page, as Figure 1 shows.

However, if interactive options make a Web page seem overly complex, the benefits of interactivity are lost. For example, the NASA home page, shown in Figure 2, offers access to an abundance of content without a user’s having to load a new page. Yet the number and variety of interactive options—expanding features, tabs, drop-down menus, and more—might be overwhelming to a user.

Are You Making It Hard to Refer to Content?

The interactive display of content can make it harder to refer to content, provide links to it, bookmark it, or share it with others. With current technology, we can provide access to content without displaying a new Web page. For instance, clicking a tab could display more content without loading a new page. In such as case, if users returned to the page, they might have to remember to click a particular tab to see the content on the tab. If the need to link to or bookmark the content were low for most users or situations, this might be fine.

However, if the need to link to or bookmark the content were high, it would be essential to provide access to the information in a way that supports linking or bookmarking. As Figure 3 shows, CNN.com provides distinct Web addresses for its tabs, even though the entire page does not reload when displaying each tab. A user could easily bookmark or share the content on any tab—and users are likely to do so with news content.

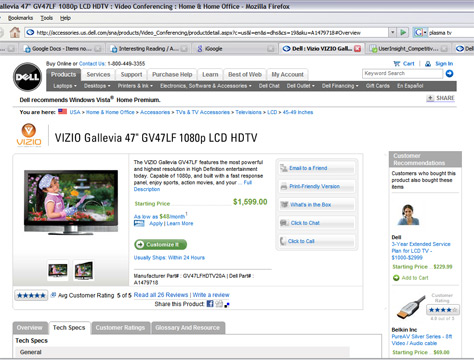

Dell.com does not have distinct Web addresses for its tabs, as Figure 4 shows. So, a customer might have some difficulty referring to the content on a specific tab or sharing it with other people who are involved in a decision to buy.

Contextual FAQs are another common example. Placing FAQs within the context of a topic or task is extremely helpful to users in the moment of performing a task. However, users who want to find the information in the FAQ later might have trouble. FAQs need to be available both in context and in a separate, easy-to-bookmark section.

Are You Making It Hard to Search for Content?

I am far from an SEO (Search Engine Optimization) expert, but I know interactively displaying content impacts search engine optimization. A page that is overwhelmingly crowded with content might fare better in search rankings than an interactive content experience, so you might want to consult an SEO expert or information resources on SEO. I suspect SEO is one factor in the current trend toward marathon-length product pages such as those on Amazon.com.

Are You Forgetting About Printing?

Consider whether users would want to print the content you are presenting interactively. For instance, the hotel details shown in Figure 5 offer some key facts about the hotel—Internet options, their pet policy, and more—that appear only when a user points to an icon. This feature lets users get more information without loading a new page. However, the information is not printable. When specifying the interactive presentation of content, we should also specify how to incorporate the content that we present interactively into a print version of a Web page.