Origin of the UX Design Practice Verticals

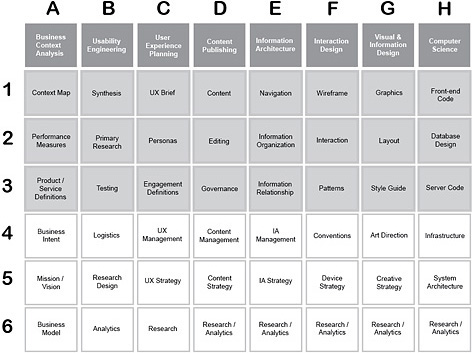

The UX Design Practice Verticals grew out of the industry’s short history as a maturing practice over the last quarter of a century or so. By the mid-’90s, UX design had become a significant HCI practice and was beginning to reveal its boundaries as well. These boundaries were both broad and deep, and the knowledge of diverse fields and subfields contributed to this practice. In 2000, Jesse James Garrett captured the breadth of UX design with his now-famous illustration, “Elements of User Experience,” shown in Figure 1.

According to Garrett, the subject matter of each horizontal plane defines the foundational components that let us understand a problem space and craft an intentional user experience design solution for it. In other words, this is not the entire list of subjects, but includes the fundamental subjects whose branches comprehend many other areas of interest. For example, the User Needs element might trigger conversations regarding accessibility, usability studies, ethnographic research, contextual inquiries, and other methods of gathering qualitative and quantitative insights about the human experience and computer interactions.

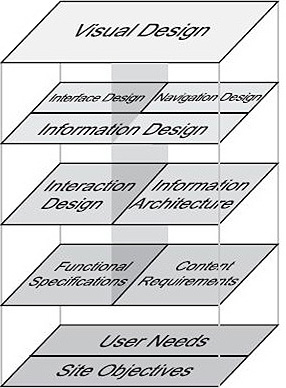

In 2004, amid the continuing debate about information architecture’s dominion over the elements in Garrett’s UX-centered diagram, Peter Boersma brought additional clarity to the conversation with a perspective that resonated with a large audience. In his 2004 blog post, “T-Model: Big IA Is Now UX,”![]() Boersma expressed how, as a practice, UX design leverages only a part of each of its related fields, as Figure 2 shows. Then, in 2006, in in a paper titled, “User Experience: The Next Step for IA’s?” it appeared that Boersma was reducing Garrett’s ten UX design elements to nine. He used a vertical metaphor to illustrate what I’ll call the Boersma assertion, summarizing it as follows:

Boersma expressed how, as a practice, UX design leverages only a part of each of its related fields, as Figure 2 shows. Then, in 2006, in in a paper titled, “User Experience: The Next Step for IA’s?” it appeared that Boersma was reducing Garrett’s ten UX design elements to nine. He used a vertical metaphor to illustrate what I’ll call the Boersma assertion, summarizing it as follows:

- UX design leverages methods from several pre-existing fields.

- UX design consists primarily of the shallow methods of each field.

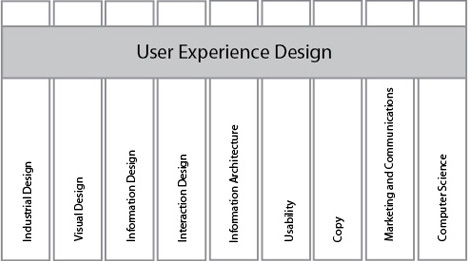

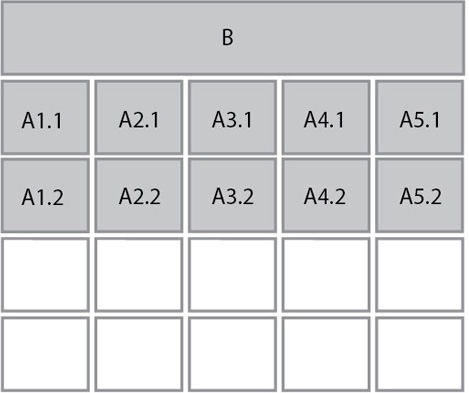

Figure 3 is a more abstract version of Boersma’s illustration, in which the gray area (A) in each column represents the overlapping interests of UX design across what Boersma refers to as the shallow methods of any given field. The gray area located outside each vertical (B) represents new HCI architecture and design methods that originated in the practice of UX design.

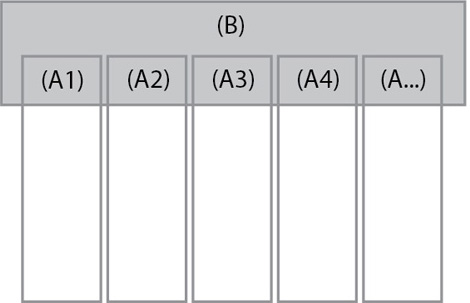

Originally, the conceptual motivation of Boersma’s diagram was to show a delineation between the core activities of information architecture and those of UX design, which evolved into distinguishing UX design from other fields as well. However, Boersma’s T-model diagram offers, at best, only an abstract delineation of where UX design methods overlap with other fields. Because his T-model diagram does not explore each vertical intersection more explicitly, in the manner that Figure 4 suggests, it leaves the identity of the overlapping methods of UX design and each respective field in question. Likely, this is a question for which many UX professionals are seeking an answer—and this is where the UX Design Practice Verticals come in handy.

While other models exist that illustrate the range of UX design, there are few, if any, that originated as a result of scientific inquiry—as the DSIA UX Design Practice Verticals have. The benefit of a scientific inquiry is that its result will either produce more evidence, a proof, or more questions, or falsify some prior assertion such as a belief or theory or knowledge such as an established empirical observation or practice.

Until 2011, the Boersma assertion was only a loosely supported belief that many had adopted, and Figure 2 shows its most highly developed representation. However, in 2011, I investigated the informational integrity of Boersma’s assertion by exposing greater granularity in each vertical to reveal the explicit intersections across the shallow areas that Boersma predicted. This was the first effort to corroborate Boersma’s original idea.

While my assessment resulted in a recategorization of the fields that Boersma had delineated and reduced the number of fields to eight, it also proved that it was possible to model Boersma’s assertion. The UX Design Practice Verticals distinguish A—the shallow overlapping methods of other fields—from B—the unique UX design activities.

Now that you have a historical overview, I’ll explain the practice verticals.