Merriam-Webster defines a system as “a set of connected things or parts forming a complex whole.” Computers and the networks that connect them are incredibly and increasingly complex. Over several decades, they have matured, and we now entrust them with the masterful application of computation, signaling, mechanization, encoding, processing, and information output. These are the embodiment of the word system.

Historically, businesses—and society at large—have benefited tremendously from computing and networking technologies. As a result, engineers give thoughtful consideration to their architecture and design. Systems architects and engineers are highly respected professionals, and the leaders among them consult on strategy at the highest level in any company that has even the slightest computing and networking infrastructure. At this level, information systems (IS) failure is not an option. However, this was not always the case.

In its earliest applications, the primary purpose of electronic computing was to crunch numbers for accounting and financial analysis. System failure, in this case, was disruptive, but manageable. However, when technology moved into the domains of sales and marketing, failing to complete transactions and generate revenue introduced a new level of risk.

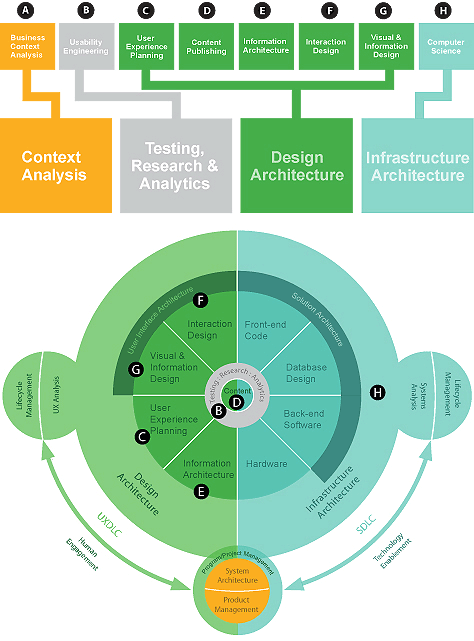

Today, enterprise information systems provide digital scaffolding throughout entire businesses and are vital to complex business operations and digital product success. In some cases, information systems offer competitive advantage; in others, opportunities for innovation. As a result, sound IT systems strategy constitutes a range of disciplines that are essential to maintaining reliability, including, but not limited to, systems architecture and design, software engineering, data management, and security.

A New System

Factoring in human beings has not always equaled human factors. Conventional thinking asserts that professions relating to information systems consider people as a design factor. However, in practice, the creation of IT systems primarily concerns the transactional states of machines and software and their ability to improve business processes and decision making. There is little regard for the user-interface functions that would produce acceptable human engagement.

Thus, while we may factor people into the design of information systems, the extent to which we systematically view actual human factors such as perception, cognition, culture, and accessibility is limited—and, as a result, teams commonly attend to them only after they’ve designed and built the system functionality. This approach is a sure route to perpetual iterations and a huge backlog of user-interface enhancements—assuming that you have a research and analytics practice in place to expose opportunities or discover UI shortcomings.

While computer-to-computer communications remain indispensable, we should not dismiss human-computer interaction (HCI), because it bears risks that can be equally disruptive to business performance. Some risks that correlate with human-computer interaction include poor security, slow performance, inconsistent affordances for interactions, and poor communications.