- Picture this: You run a UX agency and have been talking to a client about creating a mobile application that would improve communication between the company’s management team and employees.

- Some background: Management has received complaints that employees haven’t memorized all of the necessary processes and procedures. Employees need to know the answers to specific questions about company policies to successfully complete their tasks—such as making a sale or delivering a product off the truck. Since employees are mostly in the field, they rarely have access to a computer to look up or verify company procedures and policies.

- Our goal: To discover what information employees need from their corporate office—and why—when they’re out in the field.

- Our recommendation: To conduct a quick round of ethnography-like research—shadowing people as they go about their day to see what they want and need—before moving on to designing a solution.

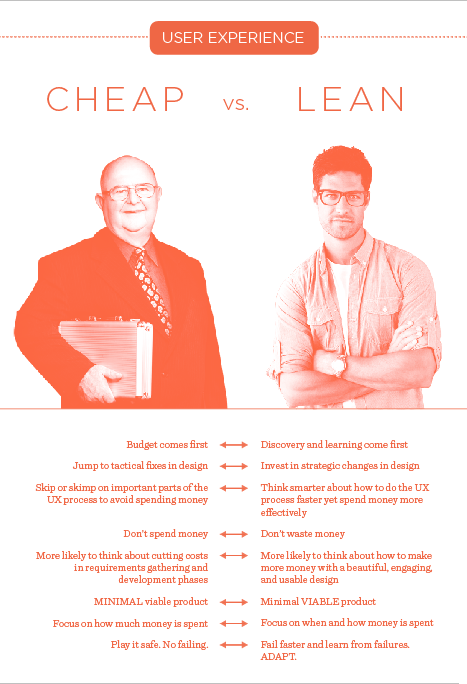

- The client’s response: Their management team is focusing on Lean UX. Spending money for an outside UX firm to conduct an ethnography study and provide a deliverable describing what the employees need doesn’t seem lean to them. They would rather start designing now, then do some quick usability testing to make sure their design works.

A Super-Truncated History of Lean UX

Look, at my agency, we are huge fans of being Lean. Many great ideas and smarter processes have come from our thinking about Lean UX—from replacing the traditional waterfall model of product development with Lean and agile models [1]; to creating a single product team that encompasses design, management, and development [2]; to meeting customer demands by building new businesses and products more quickly and effectively [3]; as well as the Pain-Driven Design (PDD) methodology that Laura Klein introduced in UX for Lean Startups. [4]

Product teams can implement solutions faster—by adhering to short, iterative, low-fidelity development cycles; seek feedback early and often—which anyone who has been in the field of user experience for more than a year knows is the best way to go; and fully integrate UX professionals—so rather than fighting with product and development people, we’re collaborating with them.

However, two years ago, Jeff Gothelf surmised that being Lean would be difficult for a UX agency:

“For internal software/design organizations, the transition to Lean UX is well within reach. You are in the problem-solving business, and you don’t solve problems with design documentation. You solve them with elegant, efficient, and sophisticated software. … Interactive agencies have it a bit tougher because they are in the deliverables business. They get paid for their documentation and spend a lot of time creating it. A specialist creates each document, and they charge for that time. Reducing those efforts means reducing revenue.” [5]

As I thought two years ago and still think today, Jeff seems to believe that agencies are inherently averse to Lean and prone to focusing on extraneous, costly details. In his recent book, Lean UX: Applying Lean Principles to Improve User Experience, Jeff states:

“To make Lean UX work in an agency, everyone involved in an engagement must focus on maximizing two factors: increasing collaboration between client and agency, and working to change the focus from outputs to outcomes.

“Some agencies attempt to focus on outcomes by experimenting with a move away from fixed-scope and deliverable-based contracts. Instead, their engagements are based on simple time-and-materials agreements, or more radically, on outcome-based contracts. In either case, the team is freed to spend their time iterating toward a specific goal, not just a deliverable.”

As an agency, we completely agree with the philosophy of breaking down walls and working with clients, not for them. Involving clients early and often promises the same sorts of benefits as involving users early and often—it makes us smarter and faster. Collaborating with clients helps us move from being outsiders to being insiders and provides us a better understanding of the business need and the problem they’re asking us to address.

We also agree that, in many cases, you can just start by designing. Sometimes, no research is necessary. We’ve done many kickoff meetings where sketches were our deliverables—simply because we hit on an appropriate strategy for navigation or interaction right away. I’ve never wasted time doing user research just for the sake of doing it. My goal in doing research has always been to get clients answers for their burning questions—and ultimately, to solve their problems.

But, what we do isn’t just about solving challenging problems. It’s about creating new, more meaningful experiences—and that may come with a new set of challenges. Companies often bring in agencies to come up with better ideas. I’m not saying that’s right or that all agencies can do this, but there’s a reason why agencies exist and have been experiencing growth over the past few years.

While being Lean is awesome, being innovative means that spending time and money on smart research and devoting ample time to thinking through the problem space can sometimes mean the difference between a good design and a great design. Our focus is not just on making something usable, but on creating value for a business and really impacting people’s lives.

Deliverables Are Not the Ogre in This Tale About Agencies

Yes, agencies typically end engagements with deliverables. But, we don't charge our clients just for the deliverables. We charge them for the value that we provide and the objective insights, fresh perspectives, and innovative solutions that we offer. We provide an innovative vision for an exceptional user experience in the form of an artifact, or deliverable. The presentation of our insights and recommendations in a solid deliverable can often be the tipping point for organizations seeking to change their product or experience for the better.

Sometimes, we create deliverables that comprise only a few slides—which actually takes longer to produce than a 50-slide presentation that offers data, but not insights. Creating these shorter, more impactful deliverables is time intensive, but also worthwhile. We’ve often seen our clients embed them into their own presentations to help the larger organization understand and socialize our research findings and design solutions.

We don’t create deliverables just to show that we’ve thought about a problem in great detail. Obviously, we do think about design problems a lot, but we don’t need to prove this through deliverables. Rather, we need to prove this by producing a beautiful, elegant, fully thought–out design solution. (It’s not about output, it’s about outcomes, as Gothelf notes.) [5]

In the case I described earlier, we knew that doing a legitimate round of research—not just GOOBing it—would help inform our design strategy with actual data from users on what they needed. We were able to convince the client to follow our recommendations, and our ethnographic study revealed a solution that was completely different from what the team had originally conceived. Prior to our conducting this research, the internal design team had been thinking about a mobile-friendly intranet from which field workers could access information. However, our study exposed an opportunity to redefine the intranet as a texting solution that would allow field employees to quickly and easily ask questions about benefits, processes, and tools, using their phones.

Other ideas that our research inspired include FAQs that people could access on wearable, smart devices and embedding smarter technology in the products themselves, so there would be less burden on the field team. We subsequently did concept testing and usability testing to validate that our design solution solved the client’s process problems.

When using our design solution, the field team had fewer unanswered questions and were quickly able to get answers to the questions that they did have. Our design solution also fulfilled the softer goal of making the field team feel more integrated into the company’s culture and persuading them that the corporation really cared about taking care of them. In 15 years as a consultant, I haven’t seen any intranet excite employees as much as this solution did.

Sure, doing the research cost the company money, but that money was well spent. If we had not conducted the research, they would have gone down a totally different and erroneous path. The deliverables from each phase of our research were also valuable, in that they helped the larger team understand why we were investing in this audience and to get on board with our solution. The criteria for being Lean are to get to the best answer in a way that’s faster and smarter. In this case, without a serious dive into the needs of these users through research, reaching the design solution would have been faster, but not smarter or better.

Now, here’s the fun part of this whole scenario: Altogether, the design solution and three rounds of the research took only four and a half weeks—deliverables included.

Some of you might think that we would charge less for this project since we completed it in just four weeks rather than 12 to 15 weeks. Those of you who do think that would be, in my 3-year-old’s words, “silly willies.”

If we can think faster, solve problems faster, and measure and validate faster, in more realistic ways, why would we take a financial hit and charge less? In this case, the ethnography took only two days because the real user needs immediately hit us, so we didn’t need to keep going just to hear the same things over and over again. We canceled the third day of interviews that we’d scheduled, came up with the concept, and used the remaining research sessions to validate our design direction. Further exploration of our ideas led to a storyboard, which we used during a day of concept testing. Then, based on our concept, we created an interactive prototype to use for usability testing.

We had meetings with the client every other day and documented the whole solution, including the rationale for our design decisions and supporting quotes and video to show where the design ideas had originated. So, we were able to co-present to the larger client team with the person who was our point of contact at the client company.

To me, that’s being a Lean agency. UX agencies can make more money by being Lean because the client pays for the value they get, not the time the agency spends on the project or the deliverables that they produce. A quick, great solution is worth more than a slow, inferior one.