Once your team gets in that place, no amount of persuasion seems to work, and the discussion can degenerate into a battle of opinions—what Steve Krug calls “religious wars”—which can break out even over how to respond to user research or usability tests. Our usual business tools—charts, graphs, and rational argument—don’t work very well when you have to convince people on both a rational and an emotional level. You might be able to overwhelm them with data, but to do that, you have to have a lot of data. You can work through a dialogue with your team to resolve such issues, but this takes a long time and is impractical if you need to persuade a lot of people at once. That’s where stories come in.

Storytelling as a way of communicating ideas isn’t just our idea. There’s a whole community around storytelling as a way to lead. Steve Denning, a former manager at the World Bank, says a story can act as a spark for an idea. In his books The Springboard![]() and Radical Management,

and Radical Management,![]() he describes the way you can use stories to introduce new ideas into an organization and get people to listen to them. He thinks they are the key to a new style of leadership that abandons command-and-control for teamwork.

he describes the way you can use stories to introduce new ideas into an organization and get people to listen to them. He thinks they are the key to a new style of leadership that abandons command-and-control for teamwork.

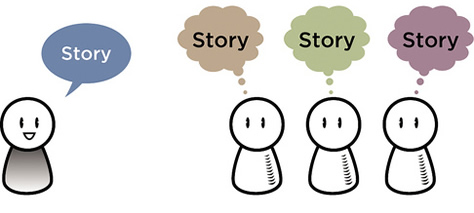

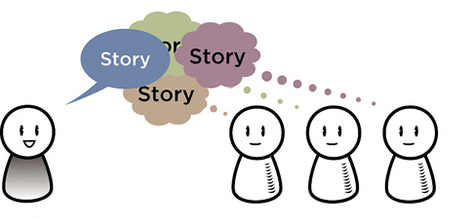

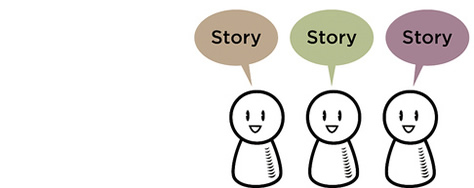

What makes stories work in a business context is the way they engage the imagination. The same thing works in user experience. A good storyteller invites listeners to enter into the world of the story and make it their own. Figures 1–4 show how this works.

Once your listeners have engaged their brain and their emotions, they’re ready to join you in a new idea.

Here are three examples of how short, targeted stories can engage your team or your management as you explain user research results or present a design idea.

Use Stories to Explain Pesky Realities

Real people have a habit of surprising us with unexpected attitudes or behavior. When you have to share counterintuitive or subtle user research, don’t drown your team in data. That sets you up for an argument—and a few data points probably won’t convince anyone on their own. Instead, use a story to present the idea from a different perspective. When crafting your story, you can use this simple structure:

- Start with a fact.

- Suggest an explanation.

- Use a juicy fragment from your user research to illustrate the point.

- End with a conclusion.

Here’s an example:

We were ready to be disappointed. We’d tried a discussion forum before, but nurses were more interested in people than technology. They used the Web, of course, but didn’t see social media as something for work. Only a few of them had phones that did more than make phone calls. Some didn’t even have Web access except at home. So, we were taken by surprise when one nurse after another got enthusiastic about some concept sketches for mobile health sites.

Gina gave us the first clue. A nurse manager for the county health system, she told us: “I’m on the move all day, and I have a huge case load. Patients are always throwing new questions at me. Yesterday, I really struggled to sort out a problem one patient was having with side effects. Though I speak a little Spanish, I just couldn’t remember the correct medical term to explain a new adjuvant the doctor wanted to try. It was so frustrating. I’d like to know it all, but there are difficult cases and new drugs. I always try to make sure I get all the specifics right, so I don’t give anyone the wrong information.”

What Gina wanted was targeted and practical: Spanish translations of medical terms, information about side effects, and dosing guidelines. She pointed at the sketch, saying, “I don’t have a phone that will do all that—yet. But if it’s really that simple…”

Instead of our team’s arguing about adoption rates of smartphones among nurses or whether medical professionals are Web savvy, our story put the data into context. The problem wasn’t what technology the nurses have, but understanding how they think about technology on the job. Stories from your research data that illustrate the real people and real contexts behind the data can be a starting point for productive discussion and brainstorming—and, in this case, a mobile Web site that would really work for this audience.

Your story doesn’t have to be long and involved. A simple, juicy fragment lets your audience get the flavor of a real person with a real point of view. Here’s what you need:

- a sympathetic character—Make sure you give a few details, so your audience can identify with the person in the story, no matter how far the character seems from your listeners. For example, our listeners may not be nurses, but everyone can identify with a chaotic, busy workday like Gina’s and having to deal with a constant stream of new information.

- a clear situation—Include enough context to set the scene, but make sure there’s room for your listeners to imagine their own small, contextual details. In our example, our listeners would be able to imagine working in a busy county health center and the challenges of low health literacy, so they wouldn’t need much help to understand Gina’s perspective.

- rich imagery—Focus on details that evoke sensory images. You want to communicate what the person’s experience is like, not the details of the activity. Gina is on her feet all day. She’s rushed. Her patients can be difficult to communicate with. The information she needs is always somewhere else.

Finally, keep your story short. You can always build on the basic story if people ask you to elaborate or answer questions. The shorter the story, the faster it is to deliver and the easier it is for your listeners to hold it all in their mind and consider it like a gem. The longer the story, the greater the risk that it will take on a life of its own and drift away from the point you are trying to make.