Perceptual Control Theory and User Intentions

“You know you’ve got a good piece of software when people use it for purposes for which the designers never intended or designed for.”—Clay Shirky

Psychology is the UX designer’s friend. We use it all the time. Our process flows and interfaces apply learning, perception, and cognition theory. Decision-making research, gamification, and emotional appeals evoke the appropriate response to the stimuli we provide. But the most useful framework for understanding users that I’ve encountered is a little-known system called Perceptual Control Theory (PCT). The invention of William Powers, an engineer with degrees in physics and psychology, PCT is based equally in cybernetics and psychology. It has recently been gaining ground as a useful framework in areas such as education and psychotherapy.

The basic premise of PCT is that human behavior is not about the behavior itself, but about reinforcing desired perception. William James said, “My experience is what I agree to attend to.” William Powers suggests that behavior is not just about agreement, but about constantly refining our experience to achieve an agreeable level of perception.

For example, a bagger at a grocery store who packs items carefully—cold with cold, fragile on top—may be reinforcing a self-perception as a caring, careful person. An executive who signs the order for a layoff may be reinforcing a self-perception as a strong, dominant person. A voter voting against his own interests may be reinforcing a perception of himself as a moral person. A programmer who writes elegant code may be reinforcing a self-perception as being a particularly rational human.

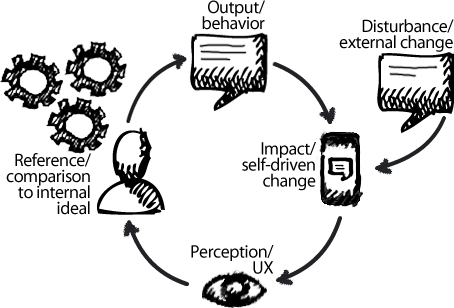

PCT suggests that a person starts off with a desired reference point for her experience. (This may change over time.) She compares her environment to that reference point and takes action to bring it closer to her desired perception. She compares the result to her reference point and acts accordingly. If something external, called a disturbance, interacts with her environment, the same comparison of input and reference point recurs, resulting in the appropriate output, or behavior. This feedback loop is the core of PCT. As Powers wrote, “Control is a process by which a person can maintain some controlled variable near a reference condition by varying actions that oppose the effects of disturbances.”

In UX terms, users actively work to optimize their own experience as much as possible. Let’s take a look at how a user-focused PCT feedback loop works, as shown in Figure 1.

PCT goes further: it reminds us that what we think a person is doing and what they think they’re doing can sometimes be very different. Powers demonstrated this very simply at a presentation to the American Education Research Association in the 1990’s.

Using a large, knotted rubber band, a chalk board, and a piece of chalk, he asked a volunteer to maintain the knot over a dot, while also holding a piece of chalk there. Powers then pulled the other end of the rubber band around in a large circle. Although Powers took care to move deliberately and not too fast, the volunteer’s chalk described a smaller circle on the board. Powers then asked the audience what the volunteer had done, and they replied that he had drawn a circle. But when Powers asked the volunteer what he’d done, he said he had held the knot over the dot.

The volunteer neither expected nor intended to draw a circle, but worked to maintain the knot’s placement. However, despite hearing the instructions and watching the demonstration, the audience had seen the visible evidence of the volunteer’s behavior, the circle, as the primary object. An analyst looking at the behavior without having heard the instructions might easily take the circle to be the purpose of the exercise.

PCT is valuable to UX designers because it helps them discover what users actually think rather than what we think they think.

Transformative Design

Several design challenges benefit directly from intention-focused design. Next, I’ll discuss how to apply intention-focused design when we’re asked to transform a site or application.

Occasionally, a UX designer or creative team receives a request to completely re-envision a site or application. Perhaps the company’s business value is changing, or the site has to adapt to the mobile world. Yet the site may have a strong following of users who are content with the site as it is, so resist change. Often UX designers offer users a more usable interaction, then are surprised by a vehement negative response. It’s a truism that users resist change. The PCT insight that people desire equilibrium at their personal reference point goes to the heart of this.

A person’s desired reference states operate in a hierarchy of importance and awareness. People work to maintain equilibrium at different levels of being. I’ve adapted this hierarchy for a compassionate animal lover from a 1982 diagram from psychologists Charles Carver and Michael Scheier:

- system concept—Be a compassionate person.

- principle—Be kind to animals.

- program—Walk the dog.

- relationship—“Dog walkingness” sequence—Keep the dog from running into traffic by pulling on his leash, tightening his choke collar. (I know, I know. Wait for it.)

- transition—Pull on the leash.

- configuration—Fingers around the leash.

- sensation—Friction of the fabric against your fingers.

- intensity—Muscle tension.

The animal lover simultaneously compares all of these perceptions to an expected, desired reference point, but those that are lower in the hierarchy can change in response to new information—provided they match the deeper expectations of system and principle. But I know that choke collar is bothering you, so let’s provide our dog owner with new information: choke collars are painful to dogs. The animal lover’s self-perception as a compassionate person and the principle of kindness to animals trumps maintaining equilibrium in the “Walk the dog” program or “dog walkingness” relationship. A new program appears: Buy a walking harness.

You have to address not just the level of environmental equilibrium, but the deeper levels of purpose and self-perception. Not doing this can result in debacles like the Netflix separation of streaming and DVD viewing. Had anyone at an empowered level said, “Customers don’t want DVDs or streaming video, they want movies and entertainment,” they might have averted the loss of customers. Great design actively engages purpose and self-perception to change the user’s environmental expectations, effectively resetting their equilibrium to a new state.