Along with all this talk about process and methodology, interaction designers spend much time distinguishing and labeling their various design practices: Is it interface design or information design? This is not surprising, because interaction design lies at the junction of several design disciplines. The resulting crossover between various specialties and issues is often muddled, understandably. There is no doubt that interaction design, as a design discipline, differs from applied human-computer interaction and cognitive psychology. These distinctions are omnipresent in the current literature.

“Interaction design’s strongest ties are to the discipline of design—not to, say human-computer interaction or cognitive psychology, although it does draw heavily on those fields. Interaction designers are designers, for good or ill.”—Dan Saffer

Saffer makes the point that interaction designers are designers not only because of process and methodology, but also because of attitude. Traces of this theme recently appeared in a thread on the IAI mailing list, “Is there a design school culture?” in which the thread instigator contemplated the difference between designers who went to art/design school and those who did not. He eloquently stated that, at times, he feels like a muggle, an outsider, who is not quite immersed in the same culture of design compared to those who had a formal design/art education. Though the author was not specifically talking about interaction design, there is a strong parallel to recent discussions on the IxDA discussion list in the “Old Guard versus New Guard” thread, which also contemplated the issue of formal design training.

At times in my career, I have certainly felt like a muggle, and certain creative types might even have called me a mudblood. But my experience has been more akin to being a squib—born into the world of design, but not quite a designer. Looking back, interaction design was for me a result of a process, not a pursuit of design. I considered interaction design a small piece of the puzzle that I relegated to an artifact, a deliverable—here’s the interaction design. In my mind, design dealt with the pursuit of aesthetics, but I always thought there had to be more. My view and practice of interaction design has certainly matured since then, but this underlying question still remains: What’s the magic and why should I use it? In other words, what puts the design in interaction design?

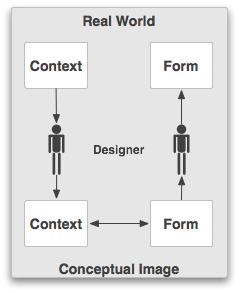

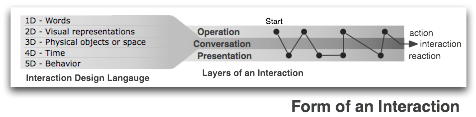

To answer this question, we need to think about the purpose of design. Design is a loaded term that has a pliable meaning. In a moment of clarity, Christopher Alexander defined the purpose of design: “The ultimate object of design is form.” This definition truly resonates with me, because it equates design with creation—specifically, the creation of something tangible, a form that traditionally takes shape as either a 2-D visual representation or a 3-D physical object or space. Interaction design sits at the convergence of these dimensions, with the addition of time (4-D) and behavior (5-D). The form of interaction design is difficult to define; it is implicit though seemingly intangible—time and behavior do not necessarily have a physical shape. To fully understand the role of design in interaction design, we must first describe its form.

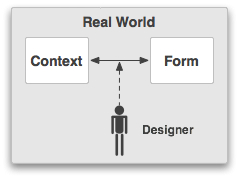

Then, we must identify the need for design. Form does not always result from a new design process. Alexander demonstrates that it can build upon existing patterns that fit within the targeted context. We see this everyday online. The Web is mostly built upon ubiquitous patterns of interaction. However, to address new problems through innovation or the modification of existing patterns, you must design. A pattern is a solution for a particular context. Furthermore, our pursuit through design is to create a good fit between form and context. The variability of context in the digital realm—the playground of interaction design—makes this pursuit more difficult. Again, to fully understand the role of design in interaction design, we must understand why we need to design.

Pondering Form

“Form follows function—that has been misunderstood. Form and function should be one joined in a spiritual union.”—Frank Lloyd Wright

“The gestalt of a digital artifact emerges in the interaction with the user over time.”—Jonas Lowgren and Erik Stolterman

Designed behavior is not invisible. Sometimes it is obfuscated; at other times, it is apparent or even obvious. Most importantly, designed behavior dictates the flow between action and reaction, which is the basis of an interaction. A user takes an action through an affordance, which in turn causes a reaction in the presentation layer. An interaction doesn’t have to be digital. For example, when I listen to a record, I must operate the turntable through the motion of lifting up the tone arm and carefully placing it on the vinyl. As soon as the needle touches the vinyl, I receive feedback in the form of sound—hopefully, it’s not too much of a crunch. Then, once a side of the record had played through, my old turntable would automatically lift the tone arm and shut down. In comparison, my new turntable, which is completely manual, infinitely continues rotating at the end of a side until I return the tone arm to its stand and press the off switch.

A user’s initial action can cause multiple reactions that occur over time. There might be a pause in behavior until a state changes, in the same way that a conversation has pauses. Conversations unfold over time, but are not continuous. A conversation has starting and stopping points. Conversation reflects interaction—the seemingly intangible component of behavior. Conversation enables communication between action and presentation. It is a conduit between action, or operation, and reaction, or presentation. These layers of an interaction converge with the multiple dimensions of an interaction design language. Together they constitute an inseparable union: the form of an interaction. As shown in Figure 1, the five dimensions of an interaction design language converge with operation, conversation, and presentation to create form.

In the introduction to Designing Interactions, Gillian Crampton Smith suggests that there are four dimensions to an interaction design language. I have added a fifth. The five dimension of the language of interaction design are:

- 1-D—words—which are interactions

- 2-D—visual representations—which include typography, diagrams, icons, and other graphics with which users interact

- 3-D—physical objects or space—with which or within which users interact

- 4-D—time—within which users interact—for example, content that changes over time such as sound, video, or animation

- 5-D—behavior—including action, or operation, and presentation, or reaction

The first three dimensions enable interaction, whereas time and behavior define interaction. It is important to note that time, as it relates to sound and other media, enables interaction as well. Typically, interactions are tangible acts—for example, pressing or clicking a button or grabbing a handle. It does not matter whether the things that afford action are virtual or physical.

The form of interaction design converges with the physical or virtual world. Most interactions require touch or movement—though voice-driven systems are one exception. A mouse is the best example of this convergence. Designed to solve the problem of interaction with the virtual world, the mouse is one part handle and one part button. It lets users instigate conversations between actions and reactions. Gestural touch is slowly replacing the mouse. Look no further than the touch pad on a laptop, which has multiple modes, depending on how many fingers you have on the pad. Multi-touch screens like that on an iPhone are also offering new ways to interact. You can swipe, press, drag, or pinch the screen to interact. Interestingly, if you rotate an iPhone, the screen automatically changes from a portrait view to a landscape view—so the entire device is itself an affordance.

Presentation is multi-dimensional, though it is mostly visual. It can also take the form of a vibration, a tone, or occur over time like music, video, or animation. Animation is a powerful communication medium. It can give the necessary pause in an interface to create a greater sense of change or affordance. Presentation affords interaction and operability in the virtual world. As a conversation unfolds, presentation might become unnecessary at times, because systems conceal some behavior from users. A ubiquitous example is ordering a book online. When you order a book, the initial reaction you receive from the system is an on-screen confirmation. Later, the e-commerce company ships your book, and the system renews the virtual conversation by sending you a shipping notification. Conversation is not always a two-way street; a third party might also be involved and instigate action or reaction, unbeknownst to the initial instigator.

The qualities of an interaction determine a user’s overall experience of and satisfaction with it. Interaction designers must consider the qualities of the multiple dimensions of interactions. Therefore, they need to have 2-D and 3-D visual and spatial literacy. Though they should ultimately focus on the quality of the conversation that is the root of behavior. Dance has similar qualities to interaction—such as line, position, space, color, tempo, melody, rhythm, and tone. According to David Malouf, you can synthesize these qualities into four base-level qualities of interaction: flow, responsiveness, context, and appropriateness. Coincidentally, the conversational postulates Sternberg described, loosely imply these four qualities:

- Maxim of Quantity—Make your contribution to a conversation as informative as required, but no more informative than is appropriate. This implies flow.

- Maxim of Quality—Your contribution to a conversation should be truthful; you are expected to say what you believe to be the case. This implies responsiveness.

- Maxim of Relation—You should make your conversation relevant to the aims of the conversation. This implies context.

- Maxim of Manner—You should try to avoid obscure expressions, vague utterances, and purposeful obfuscation of your point. This implies appropriateness.

According to Lowgren and Stolterman, additional qualities of an interaction to consider are ambiguity, surprise, parafunctionality—the means by which digital products condition our behavior—anticipation, playability, seductivity, relevance, usefulness, pliability, fluency, immersion, control/authority, elegance, transparency, efficiency, social action space, social interaction, identity and personal connectedness. You should also consider whether an interaction is dominant, subdominant, or subordinate. Finally, aesthetics and interactivity are equally important. Aesthetics can bolster seductivity and personal connectedness, thereby creating a better and more cohesive experience.