Before we dig into value innovation, let’s discuss the word value. The word is used everywhere. It’s found in almost all traditional and contemporary business books since the 1970s. In Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices, Peter Drucker discusses how customer values shift over time. He gives an example of how a teenage girl will buy a shoe for its fashion, but when she becomes a working mother, she will probably buy a shoe for its comfort and price. [1] In 1984, Michael Lanning first coined the term value proposition to explain how a firm proposes to deliver a valuable customer experience. For a business to generate wealth, it needs to offer a superior product to that of its competitors but at a manufacturing cost below what customers pay for it. That same year, Michael Porter defined the term value chain as the chain of activities that a firm operating in a specific industry performs in order to deliver a valuable product. Figure 2-4 illustrates a traditional value chain for a physical product manufacturer.

That is the business process that Toyota uses to make vehicles and that Apple uses to make computers and devices. During each of the activities in this value-chain of events, opportunities exist for a firm to outperform their competitors. But, all those terms apply to physical products. By contrast, virtual products allow for a value chain to have faster repeat loops and in some cases for the activities to happen in parallel. This is part of why traditional business strategy principles do not perfectly map to digital product strategy. When producing digital products, we must continuously research, redesign, and remarket to keep up with the rapidly evolving online marketplace, customer values, and value chains that are required to keep our products in production.

This brings us to another challenge of designing digital products: the software, apps, and other things that users find on the Internet and use everyday. As mentioned, a product needs to be valuable to customers to entice them use it. It also needs to be valuable to the business so that the business can sustain itself. However, the Internet is full of digital products for which the users don’t have to pay for the privilege of using them. If a business model is supposed to help a company achieve sustainability, how can you do that when the online marketplace is overrun with free products?

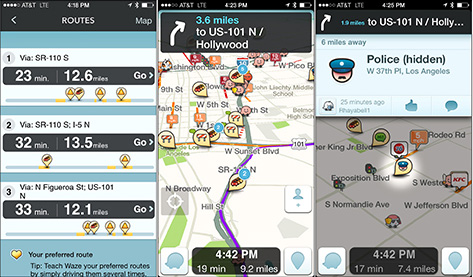

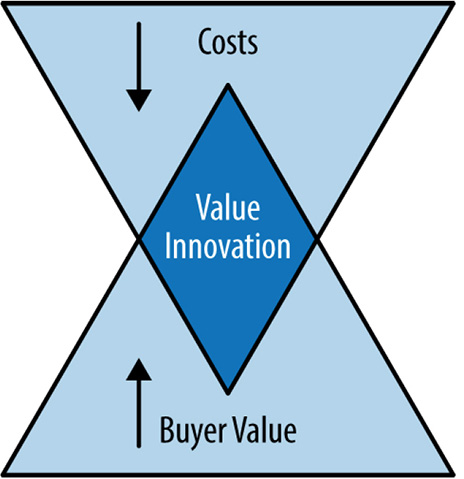

Value innovation is the key. In the book Blue Ocean Strategy, authors W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne describe value innovation as “the simultaneous pursuit of differentiation and low cost, creating a leap in value for both buyers and the company.” [2] What this means is that value innovation occurs when companies align newness with utility and price (see Figure 2-5). Companies pursue both differentiation and cost leadership to create high-value and low-cost products for the customers and stakeholders. Consider how Waze found a sustainable business model—sharing its crowd-sourced data made it lucrative to other companies such as Google. Yet, to get the data, they had to provide a new kind of value to customers for mass adoption, and that value was based entirely on taking advantage of a disruptive innovation through the UX and business model.

Disruptive innovation is a term that was coined by Clayton M. Christensen in the mid-1990s. In his book The Innovator’s Dilemma, he analyzed the value chain of high-tech companies and drew a distinction between those just doing sustaining innovation versus disruptive innovation. A sustaining innovation, he described as any innovation that enables industry leaders to do something better for their existing customers. [3] A disruptive innovation, however, is a product that their best customer potentially can’t use and therefore has substantially lower profit margins than the business might be willing to support. However, this is where disruptive innovation can blindside established competitors. Christensen says that disruptive innovation usually is “a process by which a product or service takes root initially in simple applications at the bottom of a market and then relentlessly moves up market, eventually displacing established competitors.” [4]

Innovative means doing something that is new, original, and important enough to shake up a market, and this leads us right back to the book Blue Ocean Strategy. In the book, the authors discuss their studies of 150 strategic moves spanning more than a 100 years and 30 industries. They explain how the companies behind the Ford Model T, Cirque du Soleil, and the iPod won because of how they entered blue-ocean markets instead of red-ocean markets. The sea of other competitors with similar products is known as a red ocean. Red oceans are full of sharks that compete for the same customer by offering lower prices and eventually turning a product into a commodity. In contrast, a blue ocean is uncontested territory; it is free for the taking.

In the corporate world, the impulse to compete by destroying your rivals is rooted in military strategy. In war, the fight typically plays out over a specific terrain. The battle gets bloody when one side wants what the other side has—whether it be oil, land, shelf space, or eyeballs. In a blue ocean, the opportunity is not constrained by traditional boundaries. It’s about breaking a few rules that aren’t quite rules yet or even inventing your own game that creates an uncontested new marketplace and space for users to roam.

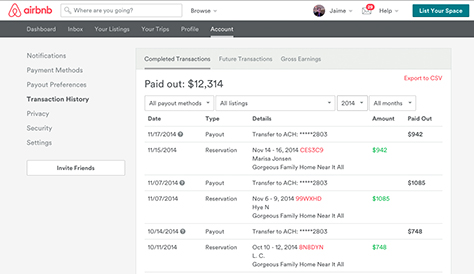

When we transpose Blue Ocean Strategy to the world of digital products, we must admit that there are bigger opportunities in unknown market spaces. A perfect example of a company that took advantage of a blue-ocean market is Airbnb. Airbnb is a community marketplace for people to list, discover, and book sublets of practically anything from a tree house in Los Angeles to a castle in France. What’s amazing about this is that its value proposition has completely disrupted the travel industry (see Figure 2-6). [5] It’s affecting the profit margins of hotels so much so that Airbnb was banned in New York City. Its value proposition is so addictive that as soon as customers try it, it’s hard to go back to the old way of booking a place to stay or subletting a property.

Airbnb achieves this value innovation by coupling a killer UX design with a tantalizing value proposition. And, as I mentioned earlier, true value innovation occurs when the UX and business model intersect. In this case, they intersected in a blue ocean because of how Airbnb broke and reinvented some rules.

For example, Craig’s List was a primary means for users to sublet before Airbnb, but it was a generally creepy endeavor. There were no user profiles. There was no way to verify anything about the host or guest in the transaction. Yet, that was the norm! However, Airbnb enabled a free-market, subeconomy in which quality and trust were given high value in the UX, much like in Amazon, Yelp, and eBay. Airbnb’s entire UX was built around the idea of ensuring that each guest and host was a good customer. It required its users to change their mental models. Formerly unwritten social etiquette now had to come into play if users were to host strangers or stay in a stranger’s home and for both parties to feel good about it.

For instance, I just came back from a weekend in San Francisco with my family. Instead of booking a hotel that would have cost us upward of $1,200 (two rooms for two nights at a 3.5 star hotel), we used Airbnb and spent half of that. For us, though, it wasn’t just about saving money. It was about being in a gorgeous and spacious two-bedroom home closer to the locals and their foodie restaurants. The six percent [6] commission fee we paid to Airbnb was negligible. Interestingly, the corporate lawyer who owned this San Francisco home was off in Paris with her family. She was also staying at an Airbnb, which could have been paid for using some of the revenue ($550-plus) from her transaction with us. Everybody won! Except, of course, the hotels that lost our business.

Airbnb’s business strategy is that they cater to both sides of their two-sided market—the people who list their homes and those who book places to stay. They offer incredible value through feature sets like easy calendaring tools, map integration for browsing, and, most crucially, a seamless transactional system that had not been previously offered by other competitors like VRBO, Homeaway, or Craig’s List. Ultimately Airbnb offered a more usable platform that minimized the risk of dealing with scary people coupled with fair market value pricing. All of this added up to serious disruption through value innovation for all customers and stakeholders in the online andoffline experience. That’s why it is winning so decisively.

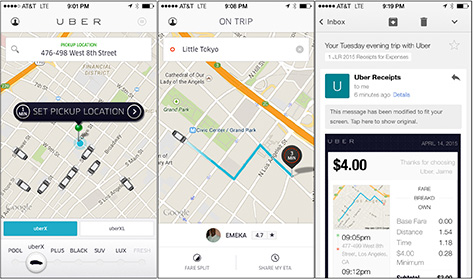

There are many other products causing widespread disruption to the status quo through their combined value innovation of cost leadership and differentiation in blue-ocean marketplaces. And through their UX strategies, they are ultimately making people’s lives easier, bringing together customers in new ways and smashing mental models. Companies such as Airbnb, Kickstarter, and Eventbrite have completely upended how people rent homes, fund business ventures, and organize events, respectively. In fact, Eventbrite is how I tested my hypothesis that there were people out there with a thirst for knowledge about UX strategy. Using its interface, I quickly set up a 60-seat lecture at the price of $40 per person, and sold it out. If I didn’t have Eventbrite to experiment with as a promotional platform, there might have been no book for Jaime Levy. Thank you Eventbrite for enabling the one value innovation that other platforms like Meetup failed to offer: the ability to host paid ticketed events.