What Is Parallel Design?

Parallel design mirrors genetic algorithms by starting with a large pool of ideas, evaluating these ideas using a set of heuristics, then selecting the fittest ideas to create a new generation of ideas. Along the way, you can add completely new or derivative ideas—similar to genetic mutations in natural evolution. You then evaluate these new ideas using the same fitness criteria. If only the fittest traits of any given generation inspire the next generation of ideas, presumably the end result is an overall population of ideas that is more robust and optimal than its predecessors.

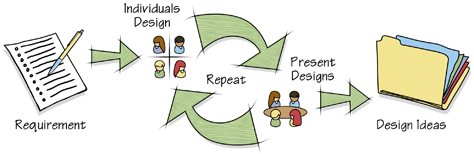

At the most basic level, the parallel design process breaks down into these steps:

- Design independently.

- Present all designs.

- Evaluate the designs.

- Repeat this process, building on what you’ve learned during the last design, presentation, and evaluation cycle.

Typically, a UX design group goes through a minimum of four such design, presentation, and evaluation cycles; at which point, independent designs should begin to converge on a common solution.

While this seemed like a potentially effective way of generating many design ideas quickly, I had found it difficult to incorporate this approach into my design projects. For one thing, I had initially understood this process to be a tool for UX designers—meaning all participants would be UX design professionals. Later, I discovered that McGrew had actually conducted parallel design sessions with nondesigners, including project managers, subject-matter experts, technical writers, and users. Even so, my fortuitous oversight inspired me to reach my own conclusions on how to expand parallel design into an inclusive and collaborative process.

McGrew’s process also called for ten people to participate over one or two days. It would be difficult to regularly fit a process requiring the participation of ten people for two days into the schedule of most UX design projects. I needed a lightweight process I could use early and often.

In a typical design cycle, internal and external stakeholders evaluate design proposals from a product designer or a UX design team. The feedback from these evaluations influences design revisions. This iterative process can take days, weeks, or longer and continues until a team reaches consensus and agrees upon a design approach. I wanted a process that essentially attempts to compress an iterative design cycle into a single half-day collaboration session. By including participants from other disciplines on a product team, as well as users, we could incorporate their expertise, different points of view, and feedback into the final design.

The parallel design process also frames the task of designing solutions for problems as a collective one, which is not solely the domain of UX designers. Teammates from outside a UX design organization can become active participants in the design space. This can help build team consensus around design solutions. Plus, participating in a creative activity together helps participants from different disciplines to better understand one another’s viewpoints.

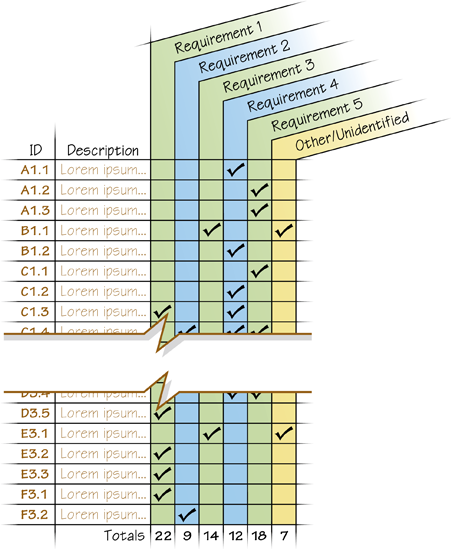

This emphasis on cross-discipline participation caused me to question the need for the usability fitness function in McGrew’s process—which is a set of up to 30 heuristics a team uses to evaluate and collectively score every design after each design cycle. The higher the score the fitter a design. This evaluation process encourages group discussion and provides an opportunity for communicating human-factors engineering principles. Though I think this can be a valid and effective approach, it can also be a potential bottleneck in the process.

First, one cannot assume nondesign professionals participating in a parallel design session know how to conduct a heuristic analysis. While one could use a parallel design session as an opportunity to teach participants that skill, I didn’t see that as the best use of our time. I wanted to focus on idea generation rather than evaluation—or worse, spending time teaching heuristic analysis to people who would have little use for that skill in their day-to-day work. Second, scoring every design in each generation on up to 30 heuristics would be very time consuming. For example, ten participants in a collaborative parallel design session that produces four generations of designs might need to consider as many as 1200 individual scores! So, even though I’ve often found heuristic analysis useful, I wanted to find an alternative approach that would allow the design process to focus on maximizing idea generation. The approach I decided to take was twofold:

- Limit the evaluation criteria to a very small set of clear requirements.

- Do no group evaluations during the design and presentation cycles.

At this point, I had all the components in place for what I call a collaborative parallel design process. I’ll provide more details on this approach throughout the remainder of this article.

A Collaborative Parallel Design Process

My collaborative parallel design process comprises the following steps:

- Identify a problem to work on.

- Gather together a team of participants.

- Introduce the participants to one another.

- Review the requirements and evaluation criteria for a design problem.

- Design independently for 10 minutes.

- Present all participants’ design ideas to the team, allowing each participant 5 minutes.

- Others can ask clarification questions, if necessary.

- This is not a critical review session! Instead, evaluate through iteration.

- Repeat the design and presentation cycle at least four times, ensuring each participant builds on at least one idea someone else has presented.

- Have a group discussion about the final designs.

Figure 1 shows a diagram of this collaborative parallel design process.

Preparing for a Collaborative Parallel Design Session

I’ve found six people to be the ideal number of participants for a half-day, collaborative parallel design session. That’s enough to get a good cross-section of ideas, but still small enough to keep things moving along at a good pace. If you find that many more than six people want to participate, consider running multiple sessions. The collaborative parallel design process focuses on harvesting the ideas of individuals, so avoid doing group design sessions. Although group design is a valid approach, sometimes the group dynamic is not conducive to getting all ideas heard, and our goal is to maximize idea generation.

Participants require time and information to prepare for a collaborative parallel design session. They need to understand both what to expect from the session itself and the requirements surrounding the design problem the session is to address.

When inviting people to participate, I briefly explain the 8-step collaborative parallel design process I outlined earlier. I also note that participation is totally voluntary. People need to know from the start that their opinions are valued, so I let everyone know that the team is intentionally diverse. The wording of one of my invitations was as follows:

I’ve tried to pick a varied cross-section of people to participate. So if you’re thinking, But I’m not a designer, that’s what I intended. Your ideas are equally important to the success of the process.

Finally, I tell everyone that this process guarantees no specific outcomes for a released product. Ideas transform, business demands fluctuate, and change is constant, so it’s impossible to say when, how, or whether an idea from a project’s early ideation phase would ever get implemented. I want to assure participants that the process is important, even if it’s not apparent down the line how it influenced the final product.

When I conduct a collaborative parallel design session, I post the following points in the room for participants to keep in mind throughout the process:

- Good ideas can come from bad designs. So don’t throw away any of your ideas. There is no telling how ideas can inspire.

- Part of an idea is also valuable. Maybe you can’t see a solution to the whole problem, but have a thought about how to solve one part of it. Capture that thought. Exploring it may lead you or someone else to a complete solution.

- Listen, learn, and be inspired. For collaborative parallel design to work, each generation of designs must inspire the next. This means it’s critical for you to be an attentive observer while others are sharing their ideas. Keep an open mind.

- Feel free to fail. People continually self-edit, because they want to avoid being wrong, but we learn the most from failure. A collaborative parallel design session is an environment in which everyone should feel free to fail.

- Have fun!

At the end of our last collaborative parallel design session, everyone said what fun they had participating. Done right, a collaborative parallel design session really should be an enjoyable experience all around.

Since collaborative parallel design is simple, you can hold sessions often, so team members quickly become familiar with the process. Over time, this should greatly reduce the amount of preparation time you’ll need for each session.