Inspiration from an Unexpected Source

When I found myself trapped in déjà vu and needing a new perspective, I turned to theory I had learned in a directing class for inspiration—and ironically, direction. I realized I might gain insight on the lead role I was playing if I thought about how my role correlated to that of a theatrical director.

You may ask, What does directing have to do with creating a user interface design? Well, we know a director is responsible for the strategic vision of creative work. That’s a given. But, did you know he is also responsible for ensuring a successful outcome that both meets his vision and is in line with the producer’s desires and budget? To make that happen, a director works with the cast, crew, costume and set designers, and everyone else who contributes to a successful theatrical production to pull together a cohesive product, without losing site of his vision. It’s a complicated job. In this scenario, change director to UX lead, producer to business owner, and the rest to designers, developers, and technical writers. Is this starting to sound familiar? Though I’d found myself feeling lost, fortunately, I did find inspiration in the unlikely source of a directing class.

In my directing class, we had studied five different theorists—all with their own unique perspectives and ideas. While I absorbed all of this information in preparation for my own first directing experience—a scary story in itself, but one for another time—I found myself intrigued by how many of the concepts could translate to any creative process, not just theater.

Peter Brooks’s The Empty Space, in particular, stood out as an approach that could help define direction and purpose when doing any kind of creative work. His groundbreaking book describes the landscape of theater as he saw it in one moment in time. His categorization of the four types of productions he typically encountered—Deadly, Holy, Rough, and Immediate—slightly esoteric though it was—reinforced the need, first and foremost

- to understand the ultimate aim for the experience or design you are creating

- to continually go back to that goal if you start feeling like you are getting lost

Brooks also gives us a way to measure the success of our ultimate aim and think about a long-term strategy—if we take these things into consideration from the beginning. For me, these concepts were the lifeline I needed to pull myself out of the weeds and recenter my focus.

Sonia Moore’s book The Stanislavski System discusses what is popularly known as The Method and provides a practical guide to one of the most well-known methods for training actors. Her ideas also gave me practical points of reference for devising and implementing a design process. So, I started thinking about whether combining these two theorist’s ideas could help me formulate a solid approach to understanding how best to undertake a design project and control the direction a design takes as a creative product.

A Glimpse into the Empty Space: Delving into the Deadly

In describing his first category of theatrical production, Brooks talks about Shakespeare as a form of theater that easily lends itself to being what he calls Deadly Theatre, because people’s expectations and assumptions about what Shakespeare is have become rote and bound in tradition. We have certain expectations and preconceived notions of what the Shakespeare experience will be. When a production meets those expectations, it is considered good or perhaps even extremely successful. The problem is: It can also be a complete bore.

Most of us have had the experience of watching some tired production of Hamlet or A Midsummer Night’s Dream, haven’t we? If the director approaches the work without a fresh perspective and asks nothing more of the actors than the same old interpretation, such a production threatens to become a thing without life or energy—thus, it is, in fact, dead. Similarly, if we let our user interface (UI) designs fall into the same old patterns again and again, we do not fulfill one of our most important goals as designers—to create a user experience that is engaging.

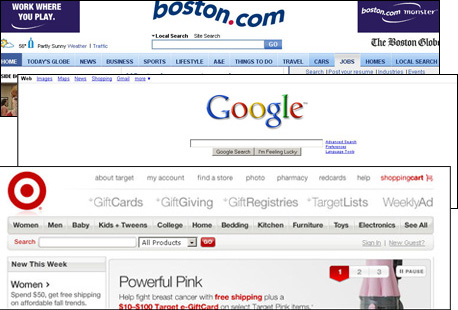

Sadly, I think some aspects of UI design—and designers themselves—have fallen into the trap of taking for granted things we do by tradition, or just because it’s the way something is done. I ask you to think of some major, successful corporate or business Web sites. Is there anything that comes to mind about their design and layout that has become too much a matter of common practice—and thus, often thought about very little during the design process? How about the standard header for a Web site or application, with its predictable logo, auxiliary links, simple search, and branding like the headers Figure 1 shows?

I worry that we are too tied to the traditional ways of presenting such standard features and, therefore, don’t stop to think whether there is something else we might do. If we are to avoid falling into the trap of creating deadly designs, we must approach every aspect of a design with a fresh eye and never simply accept a common approach as a foregone conclusion, before we’ve even begun to consider the right design for a particular situation. If you find yourself thinking you don’t need to design some part of a user interface, because it is always done a certain way, a red flag should go off in your head. It should tell you to stop and think about why the standard is a standard and whether its intents and purposes truly suit yours in a given instance. It may be that the standard is suitable—in which case, you have no reason to look further—but perhaps it isn’t. By understanding your personal choices rather than simply making the choices of the crowd, you can avoid the pitfalls of deadly design.

Achieving the Holy Grail

Brooks describes the experience of Holy Theatre—a much tougher form of theater to achieve—as one in which people “have seen the face of the invisible through an experience on the stage that transcended their own experiences.” Put simply—the invisible made visible. According to Brooks, Holy Theatre is a celebration of ritual that lets us connect at our own level, in a real way, with the higher aims of life—those higher aims being the invisible. For Brooks, Holy Theatre requires clear, direct two-way communication—between the audience and the actors.

To understand how art of any kind, but theater in particular, can communicate on this level, Brooks and his colleagues grounded their work in the ideas of Antoin Artaud, who touted gesture as a language that transcends verbal communication. They tried to understand the smallest behavior an actor could use to communicate what state he was in. Was it gesture, movement, rhythm, sound? Looking beyond written language gets more to the core of the experience—something UX professionals should care deeply about. What is Holy is clean, clear, and simple and communicates in a direct and engaging manner.

With their breakthrough products like the iPod and iPhone, shown in Figure 2, Apple has succeeded in achieving what many would call Holy Design. Apple is clearly aware of the fundamental requirements of Holy Design—clean, clear, and simple. Apple also understands that, for an experience to be Holy, it must be unique and innovative. Apple reinvents their products’ user experiences—though, like all of us, they use others’ designs as fodder for their design concepts—and drive their success by offering the next revolutionary idea.

Setting your aim on Holy Design means making a commitment to think things through anew on a continual basis—a major undertaking that potentially represents a serious organizational change. To successfully achieve Holy Design, not only do you need to focus on one idea at a time, you need to think about the idea from every perspective. Holy Design is an immersive experience, and achieving it requires starting at square one every time and working through the design process from beginning to end. Successful companies like Apple—or even Quark back in the day—know that creating a few exceptional products can make for a very successful business model—if you take the time to develop that Holy user experience again and again.

Rough and Dirty

Another of Brooks's categories of theater, Rough Theatre, is without pretense, down to earth, and gets to the “real actions” in a performance. Rough Theatre is popular theater for the common masses, or anti-theater. It requires no particular dramatic form, beautiful sets, or even an auditorium; it happens in the moment, with whatever is available. Brooks compares Rough Theatre to Surrealism, which he defines as “pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought. Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation.” Rough Theatre introduces us to the nitty-gritty realities of life and, by letting us share a common experience, makes us feel connected with our fellows. At the heart and origin of every design, I believe there exists some aspect of roughness and the desire to find the common experience that provides value. However, I caution us all to think of Rough Design as merely that—the scaffolding upon which to build a developed experience.

When I tried to think of an example of Rough UI Design, one Web site immediately popped into my head—Craigslist, shown in Figure 3. With its distinct lack of visual design, its user-based moderation, and free or minimal pricing for posts, Craigslist goes against many of the standard traditions of both design and business. As a place where users can post anything—from items for sale to rants and raves on any topic—Craigslist suits the definition of Surrealism in shocking ways, but its remaining so unrestrained and impulsive for so long is taking its toll. Too overindulgent, the site is quickly becoming a place that requires users to wade through spam and wackos to find anything of real value and relevance. This example begs the question of whether the rough-and-dirty can survive in the long term. Where and when do you draw the line and impose some restraint? While Rough Design is a viable short-term solution, you need to have a longer-term plan in mind.