We can thank Edwin Land for taking his daughter’s question seriously, leading to his creation of the first instantly gratifying, thoroughly magical Polaroid camera. The Polaroid camera forever bifurcated the product experience of photography into two tracks: cameras for professionals and personal cameras that small girls and other amateurs could easily and enjoyably use.

Perhaps, under his daughter’s adoring gaze, Land just couldn’t bear not knowing the answer to her question—but we have no way of knowing about that. What we can examine are Land’s insights in response to her very human desire. First, I’m sure Land recognized his own desire to capture memories with his child. Second, he must have understood consumers’ impatience with conventional photographic technology. Perhaps, in his Aha! moment, his train of thought looked something like what Figure 1 shows.

Capturing Memories, Instantly!

Both as the object of self-reflection and because of our need to share with others, memories are a fundamentally important part of the human journey. We go through life collecting them. Before the advent of consumer photography, we carried most of our memories in our minds—where they were subject to fading or embellishment over time.

Such is the primal nature of memories that, in aboriginal cultures around the world, people convey their memories in the form of shamans’ stories, keeping the history and knowledge of the tribe alive. In our own modern lives, we gather with our parents and our children to look at family photos and relate our memories of people from our pasts and the great deeds they did. Our photos capture the knowledge and experience we pass down through generations.

Instant gratification provides an incredible human experience. How often do we feel it? It’s the emotion we feel when we buy a funny woolen hat or down a warm beverage while out on a cold night in a foggy city. Let’s face it. In our highly time-crunched lives, instant gratification feels pretty good.

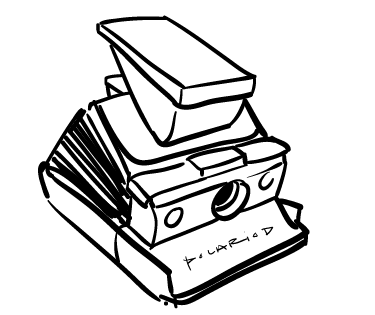

The Polaroid SX-70 instant camera, shown in Figure 2, provided the perfect user experience—a combination of capturing memories and instant gratification. The manufacturer’s inclusion of a battery and film with the camera eliminated all possible impediments to instantaneous photographic bliss. The photographic experience began with the way the camera opened up for use and the interaction of focusing an image as you looked through the viewfinder, then pressing the camera’s single red button to take a photo. Snap! Everyone experienced excited anticipation, hearing the camera’s bzzzzz-krk as you opened it to view your photo. When you were finished taking photos, the SX-70’s collapsible form snapped shut, and the way the negative space of the face slid in completed the shape of the camera.

How did it feel to instantaneously capture a moment in time on a small rectangular piece of paper? It must have felt like pocket alchemy when people took their first Polaroid photographs. In fact, it still does. Watching a ghostly photograph resolve into clarity on a Polaroid camera is a surreal experience. It’s truly sad that Polaroid is a dying technology.

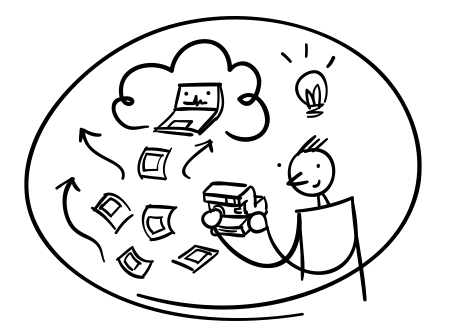

What killed the instant camera wasn’t the advent of digital photography. It was only when people found a way to share digital photographs freely online—setting our memories free—as Figure 3 illustrates, that the Polaroid really started feeling its age. Slowly, but inexorably, the noble product shifted back into the domain of hobbyists and enthusiasts, then finally descended to the end of its market cycle.