However, when you received their email messages Thursday night, you found little feedback. Plus, the comments you did get were about things like the size of the logo, the language you used in labeling some of the form fields, and opinions about what colors certain items should be. When you’re just at the wireframe stage, this is not the type of feedback you’re looking for! You’ve started to worry that perhaps the stakeholders did not think very critically about the design, so issues might surface later in the project. Now the project is behind schedule, and you’re stressed out. What went wrong?

The Importance of Stakeholder Feedback

In the previous scenario, everything started off right. Generating consensus and buy-in from stakeholders is a key to success for most design projects, so you were right to reach out to them. UX professionals are generally wary of stakeholder design, where stakeholders simply tell the UX lead what to put into a design. But you can avoid stakeholder design and still get healthy input from your business and development partners in the design process.

I’ve found that the feedback process works best when you have an opportunity to present your design ideas, then give stakeholders the opportunity to absorb the concepts and details inherent in your design. This may take some extra time in the project schedule, but it’s worth it to allow stakeholders to thoughtfully review the designs and potentially review them with other colleagues. Plus, setting specific deadlines is good project management and helps keep momentum on a project going.

The breakdown in this scenario occurred when the UX lead simply asked stakeholders to “send me feedback.” That simple instruction reflects many assumptions about stakeholder’s knowledge of the design process, areas of emphasis, and outstanding questions about the design. It’s a common mistake for UX designers, because they are familiar with the design process. Good designers understand how to provide a meaningful critique of creative ideas and recognize what level of feedback is important at various stages of the design process. Because stakeholders have a sense of ownership of a design, UX designers often assume stakeholders have these same skills and can think critically about important aspects of design and provide constructive feedback that would help improve a design. Sometimes this is a safe assumption, but not always.

5 Steps to Better Stakeholder Feedback

Fortunately, there are some simple steps UX leads can take to ensure that stakeholder feedback takes an appropriate direction.

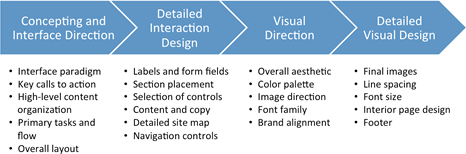

- Set the context. In my experience, many of the reasons stakeholder feedback and comments are not helpful to designers is because their comments are not appropriate at the current stage of a design process. This is especially true at the beginning of design, when a team should focus on interaction paradigms, high-level concepts, and the overall infrastructure of a design solution. This is not necessarily the fault of the reviewer. They may not be used to looking at low-fidelity wireframes or understand when in the process the team might be able to change certain things.

You can overcome this challenge by clarifying what is the current stage of your design process and the type of feedback that is most appropriate at that stage. A simple diagram, like that shown in Figure 1, can be very helpful in explaining what is appropriate for the current stage of review and provides a preview of the types of stakeholder feedback that will be most appropriate at later phases.

- Be explicit—to a point. Giving stakeholders an open-ended instruction like “send me feedback by end of day Thursday” may seem like a good way to minimize bias in the solicitation of feedback. However, given the timeframes of projects and the various possible interpretations of these instructions, I’ve found it is most helpful to list key questions or areas that stakeholders should comment on. By asking questions or simply listing areas on which you need feedback, you can guide stakeholders to providing feedback on the highest-priority design issues that need consensus. Examples of some questions might be:

- Will the design meet the business goals for the project? Why or why not?

- Please comment on the order of the proposed transactional flow.

- Are there any parts of the design that would require significantly more development resources than planned?

- Are there any design elements that legal should review?

Don’t overwhelm stakeholders with too many questions. Three to five of your most important questions should help focus their feedback. Also, start your questions with a general question about stakeholders’ overall impression of a design. Their overall assessment of the design helps frame their responses to your other questions and gives them the opportunity to highlight their major considerations regarding your design direction.