Studies have shown that people do like to have choices. Decades of psychological theory and research have demonstrated that giving people the ability to choose increases their intrinsic motivation, perceived control, task performance, and overall life satisfaction and happiness. But many of these studies offered people only a limited number of options, which they could easily differentiate and evaluate.

Current research shows that, as the number of options increases, so does the level of complexity of the decision itself. Although people are inherently attracted to having lots of choices, when it comes to actually choosing from among a large number of options, people often find themselves paralyzed and unable to make a decision. Why is it that an abundance of choice can become so overwhelming?

The Complexity of Decisions

According to Sheena Iyengar, a business professor at Columbia University, decision making involves three distinct mental tasks:

- Knowing what you want

- Understanding what options are available

- Making tradeoffs between the available options

People feel most confident in their decisions when they understand the available options and can comfortably compare and evaluate each one. It’s easiest to evaluate the options when there are only a few of them, and they are easily distinguishable from each other. As the number of options increases, the evaluation process can become overwhelming and intimidating, especially when it feels like making a choice requires expert information or skill.

People also feel a need to make the right decision—even when there might not really be a right or wrong answer. In my last column, I mentioned that people often feel they need to justify their decisions—both to themselves and to others. In abundant-choice situations, people become unsure of themselves as they grapple with the burden of judging the differences between good and bad choices. People always fear making a wrong decision, which can lead to feelings of regret. People are particularly averse to the experience of regret.

As the complexity of a decision increases, people experience conflict. They become concerned about their ability to properly evaluate the options, make the right tradeoffs between them, and make the right decision. Determining what tradeoffs to make is particularly difficult for people, especially when there are numerous options, and those options are either very similar or very different from each other. I’ll talk about this more in my next column.

What the Research Says About Abundance of Choice

Many studies have examined the effects offering either a very limited or an extensive set of options have on decision making. In a study using Godiva chocolates, [1] participants selected a chocolate from either a limited selection of six or an extensive selection of thirty chocolates. Researchers were primarily interested in learning about people’s level of satisfaction with the selection process itself, their expectations about the selection they had made—before actually consuming the chocolate—their actual level of satisfaction with their selection once they had consumed it, and their willingness to choose again at some point in the future. The findings were instructive:

- As participants made their selection, they said they experienced more enjoyment when choosing from a display of 30 rather than from a display of six options.

- However, participants who chose from a set of six options later reported feeling more satisfied with their choice, and they were more likely to want to choose again, in comparison to those who had chosen from a set of 30 options.

What’s interesting about this study is that the implications of making this decision were minor. Surely, there’s no great risk of loss in choosing the wrong chocolate. And yet, even in this study—in which choice should be more about personal preference than making the right choice—it’s apparent that giving people an abundance of choice still had a demotivating effect.

Decision Strategies

When people encounter an abundance of choice, they typically do one of two things to deal with their feeling of overload:

- They either decide not to choose—perhaps surrendering the decision to someone else.

- They adopt strategies that simplify the decision-making process.

In my last column, I talked about people’s sensitivity to the work of decision making. Their primary goal in decision making is to arrive at the best possible result with the least amount of effort. As the number of available options and the information about those options increase, people tend to consider fewer options and to process a smaller amount of the information about each of those options.

People use a variety of strategies to simplify the decision-making process. Two common strategies are

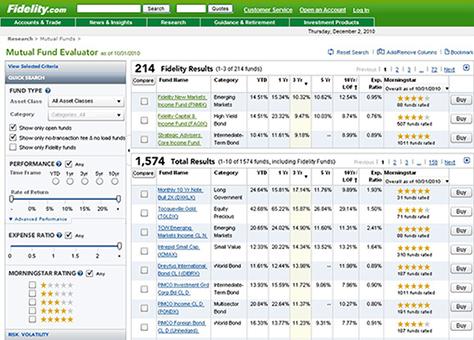

- satisficing—When people adopt a satisficing strategy, once they find the first option that meets some predefined criterion or set of criteria, they stop considering new options. Since a decision based on satisficing depends on the order in which people consider options, a different ordering of the options may yield a different decision outcome.

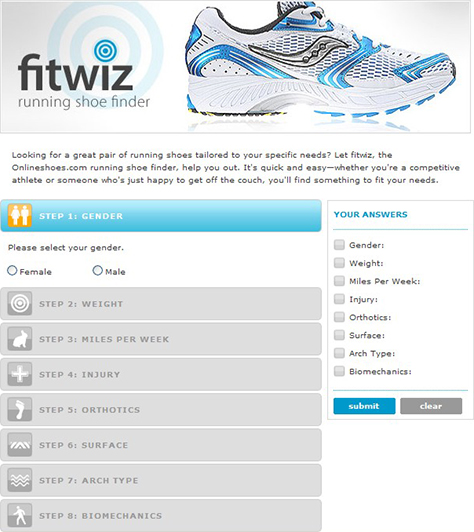

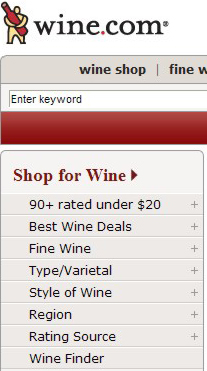

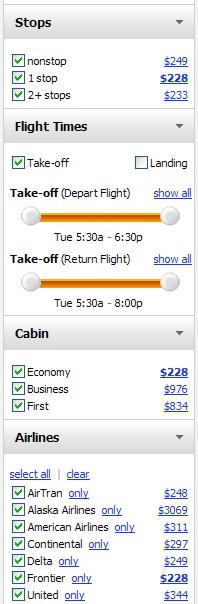

- elimination—When employing an elimination strategy, people use some criteria for the purpose of ruling out, or eliminating, options from the set of options under consideration, with the goal of reducing the size of the choice set and making a choice more manageable. An elimination strategy is a useful means of pruning down the number of options to a set a person can reasonably scrutinize in detail, thus facilitating a choice.