The second thing that our storymapping approach allowed us to see was that critical parts of the program’s story were pretty boring. For example, we saw that, while EASE had content that covered the important, or climactic, parts of the program’s story, that content was weak and less than engaging. Where the high point, or climax, should have been happening in the EASE story, we lacked content that would grab our audience and keep them engaged in the program. On the other hand, our narrative story map also let us see content strengths. For example, we were able to see that EASE had a robust listing of program activities that, even though they were’t in an ideal format, were at least in a format that they could distribute online to support the story. Thus, we were able to see content strengths and weaknesses very clearly from our map.

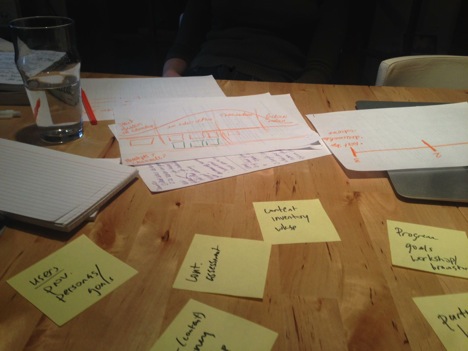

In addition to helping us to uncover content gaps, strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities, using a narrative story map enabled us to create a content roadmap extremely quickly and efficiently. Once we had assessed all of the content needs, we conducted a prioritization exercise that let us prioritize content development based on organization goals, user goals, and the level of effort that creating or updating specific content would require. This prioritized list of content would become our roadmap and inform the next phases of content production, research, and most importantly, grant-application writing.

Lastly, our narrative story map exercise worked for us: the EASE team asked us back to do more work for them. They are currently in the process of writing a grant application, which our prioritization exercise not only made easier, but helped the team to see that having people like us around helped them to be successful in their content-development efforts. A true win-win!

What Did’t Work

While structuring our engagement as a series of collaborative, rapid-fire workshops was successful overall and helped us to create a strategic vision and content roadmap in a very short period of time, there were some downsides. First, while we engaged key stakeholders within the organization and made sure that we did all of our work collaboratively, we could’t engage all key players in our process, as we would have liked to do. We prefer, whenever possible, to include lead designers, developers, writers, and anyone else who will play a key role in a project early on, so they can provide their input and we can get everyone’s buy-in. However, since we were not able to include all of these players, it’s possible that the team might not be able to reap all of the benefits that the workshops could have provided.

The second downside to working so quickly was that we did not get the chance to get out of the building, talk to users, and validate our hypotheses. Yes, our educated guesses were especially well informed because of the sound structure that we established through the mechanism of mapping the content as a narrative story map, but they are still just our best guesses until they are proven otherwise. Likewise, while the program managers were able to provide amazing insights that helped us to craft provisional personas that we used in ranking and prioritizing content and informed our roadmap, these are just sketches until we prove that our solutions are right for the users.

A team’s hypothesizing about what the stories might be for their users is an amazing exercise to go through, but stories are most powerful when they come directly from user research. At its best, storymapping is less an exercise in creativity and more one of recording research data in a visual, logical, and highly structural manner; as stories that flow, have key plot points, and a beginning, middle, and end. At its second best, it’s a tool for recording well-considered hypotheses that you will have to test, because even the best storytellers can sometimes be off the mark.